Onegin

Our quick guide to John Cranko's bittersweet ballet.

When the bookish Tatiana meets Eugene Onegin, she is immediately besotted. Enigmatic and refined, he seems like a hero from one of her novels. Onegin rejects her, seeing only a naive country girl. Will a meeting at a ball many years later offer another chance at love?

Alexander Pushkin’s novel-in-verse has inspired many adaptations, among them Tchaikovsky’s 1879 opera, John Cranko’s 1965 ballet and a forthcoming retelling by Akram Khan. Ballet Essentials: Onegin will introduce the history, creation and themes of John Cranko's seminal ballet.

John Cranko transforms Alexander Pushkin’s bittersweet tale of first love and lost chances into a sumptuous ballet, set to a soaring arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s music. 60 years from its creation, Onegin’s exploration of unrequited affection, impulsive choices and bitter regret still breaks hearts today.

Quick Facts

Who choreographed Onegin?

The South African choreographer John Cranko choreographed Onegin. He choreographed it in 1965 for the Stuttgart Ballet.

Is Onegin based on a book?

Onegin is based on Russian poet, playwright and author Alexander Pushkin’s novel-in-verse.

What is the story of the ballet Onegin?

Onegin follows the story of the arrogant yet enigmatic Eugene Onegin and the bookish and intelligent Tatiana, as they encounter each other over the years.

Is Onegin a ballet or an opera?

Onegin is a ballet, though Pushkin’s novel-in-verse also inspired an opera, Eugene Onegin.

Who composed the music for Onegin?

While Tchaikovsky composed the score for the opera Eugene Onegin, when Cranko created his ballet, he was directed by higher powers at Stuttgart to use other music. As such, Onegin the ballet is set to an arrangement, by Kurt-Heinz Stolze, of selected Tchaikovsky works.

Characters

Eugene Onegin The titular character, Eugene Onegin is arrogant yet enigmatic.

Tatiana She is a naive young girl whose head is always in her books. The elder daughter of Madame Larina, she falls in love with Eugene Onegin at first sight.

Lensky A young poet, he is in love with Olga, Madame Larina’s younger daughter. He introduces his friend Eugene Onegin to Tatiana, Olga and their family.

Olga She is Tatiana’s younger sister and is in love with Lensky.

Madame Larina The mother of Tatiana and Olga.

Prince Gremin He is a distant relative who is in love with Tatiana.

Synopsis

ACT I

Scene 1: Madame Larina’s garden

Madame Larina, Olga and the nurse are finishing the party dresses and gossiping about Tatiana’s coming birthday festivities. Madame Larina speculates on the future. Girls from the neighbourhood arrive and play an old folk game: whoever looks into the mirror will see her beloved.

Lensky, a young poet engaged to Olga, arrives with a friend from St Petersburg.

He introduces Eugene Onegin, who, bored with the city, has come to see if the country can offer him any distraction. Tatiana, full of youthful and romantic fantasies, falls in love with the elegant stranger, so different from the country people she knows. Onegin on the other hand sees only a coltish girl who reads too many romantic novels.

Scene 2: Tatiana’s bedroom

Tatiana, her imagination aflame with impetuous first love, dreams of Onegin and writes him a passionate love letter, which she gives to the nurse to deliver.

ACT II

Scene 1: Tatiana’s birthday

The provincial gentry have come out to celebrate Tatiana’s birthday. Onegin finds the company boring. Stifling his yawns, he finds it difficult to be civil; furthermore, he is irritated by Tatiana’s letter, which he regards merely as an outburst of adolescent love. In a quiet moment he seeks out Tatiana and, telling her that he cannot love her, tears up her letter. Instead of awakening pity, Tatiana’s distress only increases his irritation. Prince Gremin, a distant relative, appears. He is in love with Tatiana, and Madame Larina hopes for a brilliant match; but Tatiana, troubled by her own heart, hardly notices her kind relative.

Onegin, in his boredom, decides to provoke Lensky by flirting with Olga, who lightheartedly joins in the teasing. But Lensky takes the matter with passionate seriousness. He challenges Onegin to a duel.

Scene 2: The duel

Tatiana and Olga try to reason with Lensky, but his high romantic ideals have been shattered by the betrayal of his friend and the fickleness of his beloved; he insists that the duel take place. Onegin kills his friend.

ACT III

Scene 1: St Petersburg

Years later, Onegin, having travelled the world in an attempt to escape from his own sense of futility, returns to St Petersburg. He is received at a ball in the palace of Prince Gremin, who has now married. Onegin is astonished to recognize in the stately and elegant Princess Tatiana, the uninteresting little country girl whom he once turned away. The enormity of his mistake and loss engulfs him; his life seems even more aimless and empty.

Scene 2: Tatiana’s boudoir

Onegin has written to Tatiana, revealing his love and asking to see her, but she does not wish to meet him. She pleads in vain with her unsuspecting husband not to leave her alone this evening. Onegin comes and declares his love for her. In spite of her emotional turmoil, Tatiana realizes that Onegin’s change of heart has come too late. Before his eyes, she tears up his letter and orders him to leave her forever.

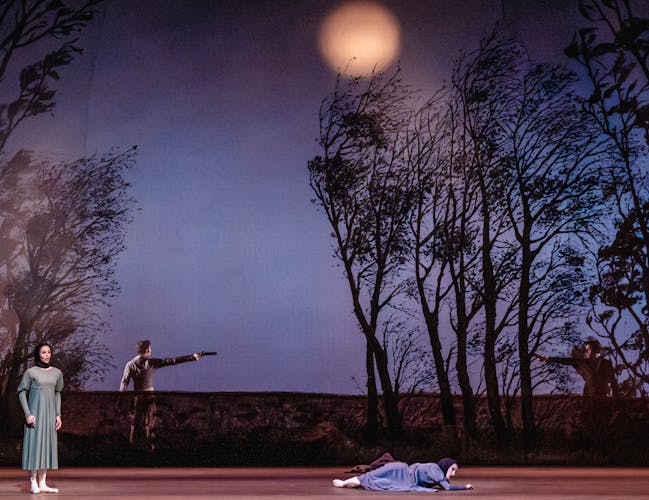

Onegin in Images

Gallery

History

The Source Material

For his ballet, Cranko chose as his source material one of the most quintessential works of Russian literature: Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

Eugene Onegin, a novel in verse, was written between 1823 and 1831 by Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837), one of the first Russian poets, who contributed to the establishment of the Russian language and its literature. It was published across several journals from the late 1820s to the early 1830s. The first complete edition was published in 1833.

The first time English-speaking audiences heard about Pushkin’s novel was in 1830, when a short article was published in The Foreign Literary Gazette. This publication discussed the first parts of the novel circulated in Russian periodicals. One phrase in the concluding paragraph of the review may explain the long love-affair between English-speaking readers and the novel. In addition to the published six parts of the novel, the review foreshadowed a new part, Onegin’s Arrival at Moscow, and described it as ‘a lively and attractive sketch of the external face of that capital’. The insights into Russian cultural life initially identified by the reviewers of The Foreign Literary Gazette, might be responsible for the popularity of Eugene Onegin in English.

Tchaikovsky’s opera

The most well-known adaptation of Eugene Onegin is Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s 1879 opera of the same name.

While Tchaikovsky may be best known today for musical contributions to the ballet world – his scores for Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker are essential to the classical ballet canon – he also had a rich creative output in the medium of opera. In the late 1860s, he began to compose operas, starting with The Voyevoda. In 1877, following a suggestion by singer Yelizaveta Lavrovskaya to create an opera based on Pushkin’s story, Tchaikovsky composed Eugene Onegin, which he finished in 1878. The opera’s first performance took place at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1881 and is still today a mainstay of operatic repertories around the world.

Translating Eugene Onegin into a ballet

Today, the version of Onegin most performed by companies worldwide can be attributed to John Cranko.

Cranko was born in South Africa in 1927. Showing a lively interest in theatre from a young age, he joined the University of Cape Town Ballet School and subsequently the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School before graduating into Sadler’s Wells Ballet (later The Royal Ballet). There he began his choreographic career, first by staging dances for operas and later choreographing for the ballet company. He was appointed resident choreographer in the 1950/51 Season.

Cranko first proposed a ballet based on Pushkin's story to the Royal Opera House board in the 1960s, but it was turned down. He would subsequently pursue the idea upon his move to Stuttgart Ballet, where in 1961, he was appointed director.

During his first year as ballet director, Stuttgart Opera commissioned a new production of Eugene Onegin, which reignited the idea of a ballet based on the same source from the back-burner of Cranko’s imagination. The Stuttgart board of directors resolutely opposed using any of the opera’s music, feeling it inappropriate to simply adapt the score for dance. Eventually, a compromise was agreed, and German composer Kurt-Heinz Stolze was commissioned to create a new full-length arrangement of a variety of Tchaikovsky’s other compositions.

Onegin had its premiere in Stuttgart, on 13 April 1965, with set and costume designs by Jürgen Rose. Cranko would subsequently revise the ballet, reshaping it into a more condensed form, which was first performed on 27 October 1967. It is this version that audiences still see performed today.

The Royal Ballet would eventually perform Onegin for the first time in 2001, with Adam Cooper as Eugene Onegin, Tamara Rojo as Tatiana, Ethan Stiefel as Lensky and Alina Cojocaru as Olga.

Choreography and Music

John Cranko’s choreography for Onegin has remained a favourite in the repertories of companies around the world.

Choreographic highlights include the letter writing scene in which Tatiana dreams of Onegin coming through a mirror, and the final pas de deux when Tatiana rejects Onegin after he realises the error of his past ways, and makes a final bid to win her heart. Both duets illustrate Cranko’s masterful storytelling and his nuanced grasp of human emotion, heightened by breathtaking and technically difficult lifts and jumps.

The lead roles of Onegin and Tatiana have posed interesting challenges to dancers interpreting them across the years. While Onegin is aloof and arrogant, he also needs to come across as charismatic and desirable to an audience imagining themselves in Tatiana’s shoes. As for Tatiana, her character grows throughout the ballet: from a naive girl lost in her fantasies, to a mature woman who finds her own strength in her struggle to make the right choice. The supporting lead roles of Lensky and Olga are similarly fascinating. It is these complexly layered personalities, embedded in Cranko’s choreography, that have given Onegin its enduring appeal since its premiere in 1965.

Onegin is set to a soaring arrangement of Tchaikovsky compositions, arranged by Kurt-Heinz Stolze. Musical highlights of the score include arrangements from sections of Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons, his opera Cherevichki, his incomplete opera of Romeo and Juliet and the symphonic poem Francesca da Rimini.

Royal Opera House Covent Garden Foundation, a charitable company limited by guarantee incorporated in England and Wales (Company number 480523) Charity Registered (Number 211775)