Creative Spotlight: Christopher Wheeldon

Read more about the life and work of Artistic Associate of The Royal Ballet, Christopher Wheeldon, in this biography.

Christopher Wheeldon has had a career marked by a restless energy and intelligence and a constant thirst for experimentation, all underpinned by rock-solid musicality, craftsmanlike, neo-classical compositional rigour, and a potent understanding of how to show the human body off to its best advantage. He has danced and been a full-time choreographer for two of the world’s A-list companies – first New York City Ballet (NYCB), and now The Royal Ballet – as well as founding his own transatlantic troupe, Morphoses.

His life

Christopher Wheeldon was born in Yeovil, Somerset, in 1973, to an engineer father and a physical therapist mother (it is impossibly tempting to see both parents’ influence on his creative instincts). He started ballet lessons at the age of eight, joined White Lodge – The Royal Ballet Lower School – at 11, and proceeded on to the Upper School five years later. In 1991, he joined The Royal Ballet and, that same year, won the Gold Medal at the prestigious Prix de Lausanne competition. In 1993, Wheeldon accepted an offer to join NYCB, and five years later was promoted to soloist.

Everything seemed to point to an increasingly glittering career as a dancer. But, having made his first piece for the American company – Slavonic Dances, for the 1997 Diamond Project – he increasingly found that it was creating choreography, rather than performing it, that most interested him. After delivering Mercurial Manoeuvres for NYCB’s spring 2000 Diamond Project, he took the plunge and retired from dancing to devote all his energies to choreography. He entered the 2000–01 season as NYCB’s first Artist in Residence.

It is, however, Wheeldon’s work for The Royal Ballet – where he became Artistic Associate in 2012 – that has tended to show him off at his most diverse. If Tryst, 2002’s collaboration with composer James MacMillan, is perhaps not one of the choreographer’s most widely remembered works, DGV: Danse à grande vitesse (2006) made exhilarating use of Michael Nyman’s propulsive score, and 2008’s ground-breaking, psychologically inquisitive Electric Counterpoint – set to a bold alternation of J.S. Bach and severe American minimalist Steve Reich – had four principals serenely dancing with pre-recorded avatars of themselves and verbally sharing their professional insecurities with the audience. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was an expert and exuberant foray into narrative comedy-fantasy, which Wheeldon counterintuitively but shrewdly speeded up in 2012’s revival by remoulding it into three acts as opposed to the original two. Trespass, his contribution to Metamorphosis: Titian 2012, was an arresting study in voyeurism, created in collaboration with fellow choreographer Alastair Marriott, composer Mark-Anthony Turnage and Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Wallinger. (Marriott also worked with Wheeldon on the London 2012 Olympics Closing Ceremony.)

In 2014, Wheeldon restaged DGV with two recent Royal Ballet successes under his belt. First performed in February 2013, Aeternum was a response to Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem that radiated a foreboding worthy of the great Kenneth MacMillan. It won Wheeldon the 2013 Olivier Award for Best New Dance, as well as the 2014 Critics’ Circle Award for classical choreography – two new additions to a mantelpiece already bowing under the weight of awards bestowed upon him on both sides of the Atlantic. Besides that recent Tony, Wheeldon has also been garlanded by, among others, Dance Magazine and Lincoln Center. He became a New York City Library Lion in 2002, an Honorary International Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2012, and was appointed OBE in the 2016 New Year’s Honours.

The Winter’s Tale, which received its premiere at Covent Garden in April 2014, added considerably to that tally, winning him the UK National Dance Award for Best Classical Choreography (among several other prizes). Made in tandem with his Alice (and Like Water for Chocolate) collaborators – composer and arranger Joby Talbot, designer Bob Crowley and lighting expert Natasha Katz – this saw Wheeldon achieve something not seen since MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, in 1965. In short, he created a full-evening work after Shakespeare that is arguably more satisfying than the original play, and one that instantly pointed the way for narrative classical ballet. It was first revived at Covent Garden in 2016, a year that also saw The Royal Ballet give its first universally acclaimed, staging of After the Rain, as well as the premiere of a new, one-act work, Strapless, based on a scandal involving John Singer Sargent’s Portrait of Madame X.

A fresh collaboration with Turnage, this narratively ambitious project further signposted the main direction in which Wheeldon now appears to be heading. And, even though he did return to more abstract territory in 2018 with his new (and recently revived) Corybantic Games, and DGV made a spectacular return to Covent Garden earlier in 2022, it is an impression that Like Water for Chocolate only further reinforced. In his gracious acceptance speech at the Tonys in 2015, he thanked his fellow nominees who, he said, ‘have pushed dance to the forefront of their shows this season, and who truly believe in the unspoken power of storytelling through dance’. As this Season’s Alice revival further proves, no choreographer active today shares this belief more passionately, or more thrillingly, than Wheeldon himself.

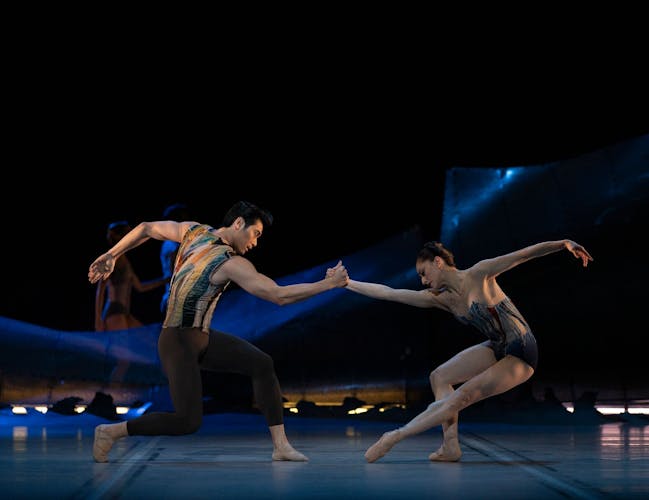

Gallery

His Style

It was in 2007 that Wheeldon made his boldest move yet. Deciding that classical ballet needed a shot in the arm, and displaying a Diaghilevian thirst for cross-discipline – not to mention trans-Atlantic – collaborative innovation, he appropriated the name of his own 2002 work and founded Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company. Launched at that year’s Vail International Dance Festival, Morphoses was to be based in both London and New York and, Wheeldon hoped, would attract not just the cream of both countries’ dancers, but also the best artists, designers and composers. Its inaugural UK run, in September 2007, at Sadler’s Wells, featured his specially created new works Fool’s Paradise and Prokofiev pas de deux, while also treating London audiences to their first experience of After the Rain, a piece whose lyrically melancholic second movement remains far and away the most successful dance setting yet of Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel. The following month, Morphoses gave its first New York performance.

Morphoses’s relentlessly hand-to-mouth existence – combined with creative differences with Wheeldon’s co-founder – ultimately proved fatal to the company, and Wheeldon ended it in 2011. (As he once told me, ‘By the end of Morphoses, we were down to, “Can we find a little lady in an attic in New York who’ll make the costumes for a third of the price?”’) Yet the inevitable disappointment of that admittedly noblest of failures was offset by the fact that those had been fecund years. In 2007, Wheeldon created the dark Hamlet fantasia Elsinore (originally known as Misericordes) for the Bolshoi. In 2009, he worked with Richard Eyre on the latter’s production of Carmen at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, while 2010 saw the premiere of his new account of The Sleeping Beauty for the Royal Danish Ballet. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland – which had its premiere on 28 February 2011, and now returns for its fifth London revival – was Wheeldon’s most remarkable collaboration to date with the British composer and arranger Joby Talbot, and was further bolstered by extraordinary designs by Bob Crowley. In May 2011, NYCB’s Manhattan rivals American Ballet Theatre gave the premiere of Wheeldon’s Thirteen Diversions, and the following January NYCB honoured him with a gala devoted entirely to his canon, including a new piece, Les Carillons.

His works

He has also created pieces for companies as distinguished and as far-flung as the Bolshoi, the Royal Danish Ballet and San Francisco Ballet, worked on Broadway, contributed to the closing ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics, and, throughout, been an insatiable collaborator and commissioner of new scores.

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in 2011, he made what was The Royal Ballet’s first new full-length work for 16 years (somehow, in the process, persuading the great stage actor Simon Russell Beale to don an outlandish purple frock and star as the Duchess). His 2014 piece, The Winter’s Tale, was the first new full-length ballet for the Covent Garden main stage since then, and proved a critical and commercial triumph. And in 2015, he returned to Broadway with An American in Paris, based on the 1951 Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron film. Opening at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris before its transfer to New York, this won him the Tony Award for Best Choreography and subsequently enjoyed a critically acclaimed run in the West End. Small wonder his new three-act adaptation of Laura Esquivel’s magic-realist novel Like Water for Chocolate was the most keenly anticipated dance event of 2022.

Wheeldon’s industriousness, and success, continued apace. In May 2001, he was appointed NYCB’s first Resident Choreographer, whereupon he proceeded to create a string of works for the company, among them Morphoses and Carousel (A Dance) (2002), Carnival of the Animals and Liturgy (2003), After the Rain and a ballet version of An American in Paris (2005), Klavier (2006) and The Nightingale and the Rose (2007). (He also found time back in 2000 to contribute dance sequences for the film Center Stage, and, in 2002, to work on a Broadway adaptation of Sweet Smell of Success.)

Taken from an article written for The Royal Ballet and Opera by Mark Monahan. Mark Monahan is Arts Editor and Chief Dance Critic of the Daily Telegraph.

Gallery

Watch more

- Main Stage

- Ballet and Dance

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works

Sensuous contemporary ballet meets the energy of musical theatre in four distinctive short works.

Royal Opera House Covent Garden Foundation, a charitable company limited by guarantee incorporated in England and Wales (Company number 480523) Charity Registered (Number 211775)