Creative Spotlight: Kenneth MacMillan

Read more about the life and work of Director and Principal Choreographer of The Royal Ballet, Kenneth MacMillan, in this biography.

No other choreographer has challenged classical ballet to express so many aspects of the human condition as Kenneth MacMillan (1929–1992). He reinvented the narrative ballet as psychological drama, able to reveal extreme states of mind. He told the stories of people whose lives were vividly realized, whether they were historical characters or imagined creations. Some of his works courted controversy, dealing with profoundly uncomfortable subjects: betrayal, guilt, madness, wanton cruelty. Other works celebrated dance for its own sake or became almost abstract meditations on love and death, set to sublime vocal music.

His life

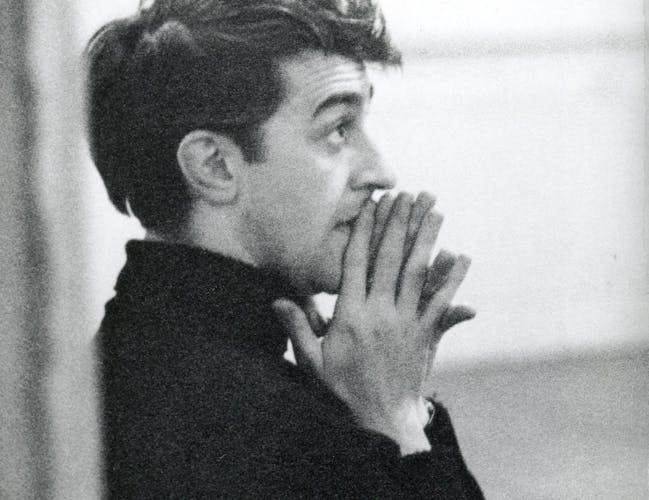

Kenneth MacMillan (1929–92) was one of the leading choreographers of his generation. His close association with The Royal Ballet began when he joined Sadler’s Wells School (now The Royal Ballet School) aged 15. He was Director of the Company 1970–77 and Principal Choreographer 1977–92.

Born in Dunfermline in Scotland, he spent his boyhood years in Great Yarmouth and Retford, where his school was evacuated during World War II. He tap-danced in end-of-the-pier competitions in Yarmouth before turning to ballet at the age of 14 in Retford. He had seen advertisements in the Dancing Times offering scholarships for boys to attend the Sadler’s Wells (now The Royal) Ballet School. MacMillan ensured that he was one of the chosen ones by pursuing ballet lessons in Yarmouth and persuading his teacher, Phyllis Adams, to enter him for an audition; he forged a letter from his (disapproving) father recommending his son’s talents. De Valois accepted him on merit, grateful for a young trainee to replace male dancers she had lost to wartime recruitment.

She was about to start a junior touring troupe, the Sadler’s Wells Opera (soon to be Theatre) Ballet, as a nursery for the main company, which moved into the Royal Opera House in 1946. MacMillan became a founder member of the Theatre Ballet, dancing a variety of roles before graduating to the senior company in time for its 1949 visit to the United States. A fine classical dancer, he appeared as Florestan in the Act III pas de trois in the historic New York opening night of The Sleeping Beauty. Increasingly, however, crippling stage fright made him long to stop performing. De Valois agreed that he should take a break and then return to the touring company in 1953. There he discovered his vocation as a choreographer.

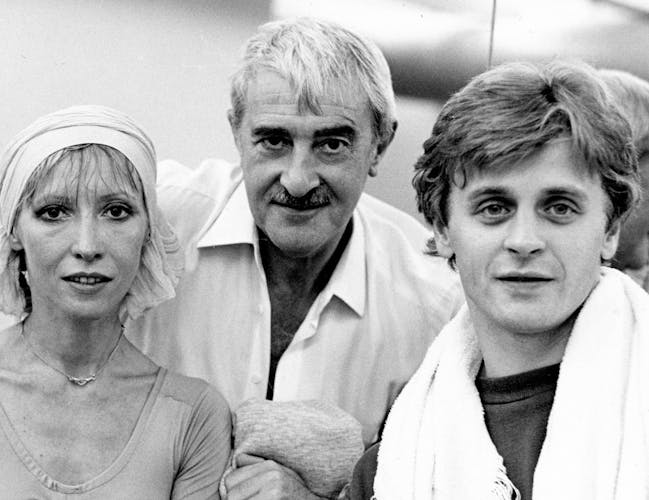

Positions away from the Company included Director of Deutsche Oper Ballet Berlin (1966–9) and Associate Director of American Ballet Theatre (1984–90). He returned to take over the directorship of The Royal Ballet from Ashton in 1970. MacMillan was the institution’s first home-grown director and choreographer, nurtured by the School and both Companies. His appointment coincided with a financial crisis, resulting in a decision to merge the two companies into one, with a small group performing new work on tour. He brought in outside choreographers (Robbins, Balanchine, Tetley, Cranko, Van Manen, Neumeier) as well as choreographing himself, both for the New Group and the enlarged resident company. During this period, he met and married Deborah Williams, an Australian artist, and they had a daughter, Charlotte, in 1973. After seven years as director, his growing frustration at trying to balance the conflicting demands of creating and administrating led to his resignation in 1977. He remained Principal Choreographer of The Royal Ballet.

On 29 October 1992, during the first night of a revival of Mayerling MacMillan died of a heart attack backstage, aged 62. His last choreography had been for the National Theatre’s production of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Carousel, for which he won a posthumous Tony Award on Broadway. He was knighted for his services to British ballet in 1983, in addition to receiving numerous awards. Since his death, his ballets have entered the repertories of more and more companies around the world, including a number of those in the former Soviet Union. His best-known narrative ballets, Romeo and Juliet and Manon, have attained the status of 20th-century classics. Among his output of more than sixty very varied works are ballets that continue to surprise, entertain and sometimes shock audiences whenever they are revived.

Gallery

His Style

He forged his own distinctive vocabulary of movement, expanding the conventions of ballet to encompass realistic, even grotesque physical reactions. In so doing, he contributed an Expressionist strand to British ballet’s heritage of dramatic choreography. As a young dancer, he had appeared in works by Ninette de Valois, Frederick Ashton, Robert Helpmann and Leonid Massine, as well as seeing Antony Tudor’s ballets performed by Ballet Rambert and American Ballet Theatre. Even before he was fully aware that he wanted to be a choreographer himself, MacMillan absorbed all he could: he grew up during an extraordinary period of creativity in modern ballet. He had first been encouraged to try his hand at choreography by his friend John Cranko, an established choreographer in the Royal Ballet and commercial world. Cranko would go on to become artistic director of the Stuttgart Ballet (1961- 1973).

In the early 1950s, a series of Sunday workshops at the Wells gave him the chance to try out his ideas in ballets – Somnambulism, Fragment and Laiderette – that proved he was more than promising.

De Valois commissioned his first professional work, Danses concertantes, for the touring company in 1955 and Marie Rambert took Laiderette into her company’s repertory. Launched as a choreographer, he was able to give up dancing. His early work, quirky and spiky, was somewhat in the manner of Roland Petit’s ballets, but MacMillan soon found his own style. He was influenced by the angry voices of Britain’s postwar playwrights (John Osborne in particular) and filmmakers, determined that he would make ballets that were relevant to his generation. Although he soon won acclaim for breaking away from fairy-tale subjects, he was a man of his time: other young choreographers were following the same path – Jerome Robbins in the United States, Maurice Béjart in Belgium, Peter Darrell in Britain.

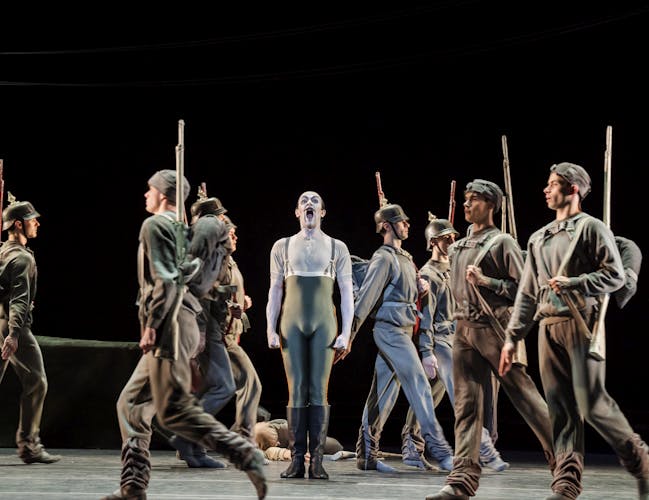

In his time as Director of The Royal Ballet, MacMillan's own works fell into two main strands: full-length House epics, such as Anastasia and Manon, and a variety of shorter ballets on themes that varied from savage (The Poltroon) to comic (Elite Syncopations). As Principal Choreographer for The Royal Ballet, producing works that grew ever darker. Mayerling told the story of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austro-Hungary and his suicide pact with his mistress; Valley of Shadows included scenes in German concentration camps; Different Drummer was based on Büchner’s brutal play Woyzeck. The Royal Ballet audiences at the time tended to resist these tortured works, although Stuttgart continued to welcome the ballets he made for them. MacMillan spent an increasing amount of his time travelling abroad: he was appointed Artistic Associate of American Ballet Theatre, where he mounted a number of his ballets, as well as creating new ones for the company, and then assumed the same post with Houston Ballet.

He reaffirmed his close ties with The Royal Ballet towards the end of the 1980s. He completed his last three-act ballet, The Prince of the Pagodas, in 1989, with the young Darcey Bussell as the heroine. The Prince of the Pagodas, with its references to The Sleeping Beauty, was MacMillan’s acknowledgment of the classical tradition that had always shaped his choreography, however far he appeared to diverge from it. A gala pas de deux for Bussell and Irek Mukhamedov, recently arrived from the Bolshoi Ballet, became the core of Winter Dreams (based on Chekhov’s Three Sisters). Mukhamedov, MacMillan’s final muse, created the role of the Foreman in The Judas Tree, a controversial ballet dealing with guilt and betrayal.

His works

MacMillan was fortunate in having the backing of De Valois, who asked him to create ballets for both her companies. In 1956–7 she gave him leave to work with American Ballet Theatre (where he made Winter’s Eve and Journey for Nora Kaye) but summoned him home when he showed signs of wanting to remain in New York. The ballet he made on his return, The Burrow (1958), was the first time he cast the young Canadian dancer, Lynn Seymour, who was to become his muse. The Burrow, which examined the behaviour of frightened people trapped in oppressive conditions, marked MacMillan out as a choreographer who could touch raw nerves. Even more searing was The Invitation (1960), depicting the sexual initiation of two youngsters, danced by Seymour and Christopher Gable. They were to be the couple on whom he created Romeo and Juliet, his first three-act ballet, in 1965.

By then he had choreographed a wide range of ballets, from plotless works such as Agon, Diversions and Symphony, to intensely dramatic ones – The Rite of Spring and Las hermanas. This last was made for the Stuttgart Ballet, now run by John Cranko, who gave MacMillan an alternative outlet for his choreography. It was Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet (mounted for the Stuttgart company in 1962) that spurred MacMillan’s ambition to create his own account of Shakespeare’s tragedy for The Royal Ballet. He had started with the balcony scene pas de deux for Seymour and Gable to dance on Canadian television even before the Royal Opera House gave the go-ahead for the complete ballet.

The premiere on 9 February 1965 was danced by Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev in the leading roles, a box office guarantee of packed houses in London and on tour. Romeo and Juliet was a huge success but MacMillan was distressed that he had no control over its casting. When he was offered the directorship of the Deutsche Oper Ballet in Berlin, he decided to accept. There he hoped to form the company after his own vision, as Cranko had done in Stuttgart. MacMillan’s period in Berlin, 1966–9, however, proved a difficult time. He battled with unfamiliar conditions, managing nonetheless to create a number of well-received ballets for the company and to mount his own productions of The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake.

Taken from an article written for The Royal Ballet and Opera by Jann Parry. Jann Parry is the author of the biography Different Drummer: the Life of Kenneth MacMillan, published by Faber & Faber.

Gallery

Watch more

- Main Stage

- Ballet and Dance

Romeo and Juliet

The greatest love story ever told – through ballet.

Royal Opera House Covent Garden Foundation, a charitable company limited by guarantee incorporated in England and Wales (Company number 480523) Charity Registered (Number 211775)