Opera Essentials: Faust

Our quick guide to Charles Gounod’s grand opera of decadence, seduction and longing, Faust.

Disillusioned with old age, Faust calls on the devil in despair. The wily Méphistophélès makes him an offer he cannot refuse: youth, wealth and the beautiful Marguerite. But before long, Faust’s newfound happiness starts to unravel, and the dream of love turns into a nightmare...

As seductive as it is damning, Gounod’s grand opera, Faust, is rich with emotional intensity and moments of profound vulnerability. With a libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, who based the opera on their play Faust et Marguerite – itself inspired by Goethe’s fantastical drama – Faust is a dramatic exploration of temptation, redemption and the human soul.

Quick Facts

Answering some of the most asked questions about Faust.

What is the story of the opera Faust?

Faust follows a weary, aged philosopher who decides to take his life. The devil Méphistophélès appears and offers him riches, youth, good looks and the love of a beautiful woman, but asks for Faust's soul in return.

Who composed the opera Faust?

Faust was composed by Charles Gounod. It had its premiere in 1859 and became one of the French composer’s most famous works, known for its soaring melodies and spectacular dramatic intensity.

What language is Faust performed in?

Faust is sung in French with English surtitles.

What is grand opera?

Grand opera is an operatic genre that emerged in Paris during the first half of the nineteenth century. Typically five acts in length, grand opera is characterised by epic historical narratives, huge choruses and dazzling stagecraft. It often also has a ballet thrown in for good measure.

Where is Faust set?

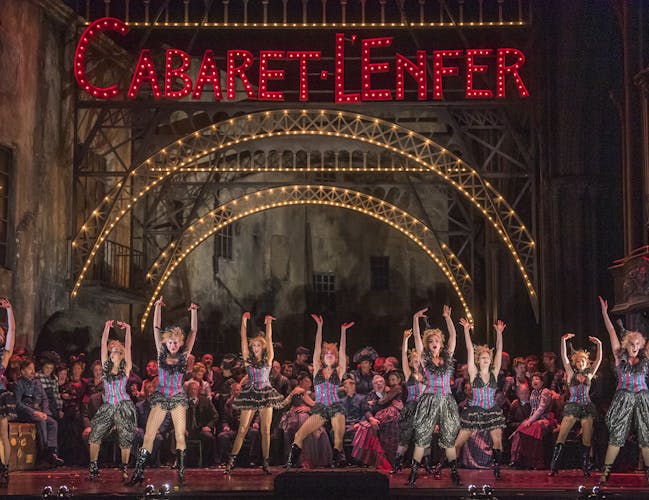

David McVicar’s Royal Ballet and Opera production is set in Paris in the 1870s. The production celebrates the increasingly modern city and draws parallels between the experiences of Faust and those of Gounod, who was always torn between religion and sensuality. Highlights include set designer Charles Edwards’ brilliant re-creations of the Cabaret de L'Enfer and the church of Saint-Séverin, sumptuous period costumes and an absinthe-fuelled demonic ballet in Act V.

What is the famous aria from Faust?

‘Le Veau d'Or’ (The Golden Calf), sung by Méphistophélès in Act II, and ‘The Jewel Song’, sung by Marguerite in Act III, are two of the most famous arias from Faust. Devilishly charming, ‘Le Veau d’Or’ is a playful, satirical song in which Méphistophélès mocks the pursuit of material wealth and indulgence. The title refers to the biblical idol of wealth and excess, symbolising the temptation of greed. In ‘The Jewel Song,’ the young and innocent Marguerite, after receiving a box of jewels from Faust (via Méphistophélès), joyfully imagines her blossoming romance, the captivating melody not only capturing Marguerite’s naïve optimism, but the dangerous allure of Faust's enchantment.

History

An Enduring Legend

The legend of Faust has intrigued artists, playwrights and composers for centuries. At its heart, the story is about a man, Faust, who makes a pact with the devil in exchange for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures – only to find himself trapped by his desires and eventually damned. The origins of the legend trace back to German folklore of the late 16th century, where the character of Faust was a scholar who sought to transcend human limits through magic. The tale has been told and retold in numerous versions, each interpreting the central themes of temptation, knowledge and damnation.

The most famous literary adaptation of the Faust legend is Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play Faust, written in two parts. Faust Part I, completed in 1808, presents the initial part of Faust’s journey, focusing on his pact with Mephistopheles and his tragic, passionate love for Gretchen (in the opera, Marguerite). The work explores themes of yearning for meaning and the complexity of human nature. Faust Part II, completed in 1832, moves into a more philosophical realm, with Faust seeking redemption and enlightenment through his encounters with mythological and allegorical figures.

Gounod’s Faust – itself inspired by French playwright (and later, the composer’s librettist) Michael Carré’s own 1850 adaptation – takes its inspiration from Part I of Goethe’s work, the composer avoiding the philosophical concerns of Part II in favour of the romantic relationship between Faust and Marguerite. Several other composers including Schumann, Boito and Mahler wrote works based on Goethe’s Faust, and predating Gounod’s opera is Hector Berlioz’s 1846 La Damnation de Faust, which stands out as a notable Romantic treatment of the story.

Behind the Libretto

Faust librettists Michel Carré and Jules Barbier were a highly successful duo, with some of their librettos becoming staples of the operatic canon. Their collaboration on Faust remains one of their most well-known works, but their partnership also produced other celebrated librettos, including that for Jacques Offenbach’s Les Contes d'Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann). A masterpiece of surreal and fantastical narrative, the libretto, based on stories by E.T.A. Hoffmann, showcases Carré and Barbier’s flair for weaving emotionally complex, dramatic stories into compelling opera. The duo was also responsible for the French adaptation of Lorenzo Da Ponte’s libretto for Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), which helped make the Italian-language opera accessible to French audiences, while maintaining much of the original's wit and charm.

Reception

Gounod’s Faust had its premiere at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris on 19 March 1859. The opera was embraced by the public, and by the start of the 20th century had become the most internationally popular opera that had ever been. But hand in hand with the opera’s popularity grew an increasing disparagement of Gounod’s version of the Faust legend, specifically the alleged trivialization of Goethe’s play. Composer Richard Wagner was among the first to deride what he termed ‘a repellent, sugary-vulgar patchwork… wedded to the music of a second-rate talent’. By the early 20th century, Faust, a victim of its own ubiquity, had become the prime operatic cliché. Still, its universal themes continue to resonate today, as does its dazzling seductive appeal.

Music and Choreography

Faust is packed with instantly memorable tunes (including the Soldiers’ Chorus in Act II) and with wonderful showpieces for the principal singers, including Faust’s heart-melting ‘Salut, demeure, chaste et pure’ and Marguerite’s brilliant Jewel Song, one of the most famous soprano arias in all opera. Faust also contains powerful dramatic ensembles, including the final scene in Act V, as Marguerite struggles to escape the temptations offered by Faust and Méphistophélès.

The orgiastic Act V ballet of Faust is also a pivotal moment in the opera, adding a sense of grandeur and spectacle to the dramatic narrative. The choreography, typically performed during scenes of revelry or decadence, enhances the opera’s atmosphere by illustrating the seductive allure of Méphistophélès’ influence over Faust and the world around him. The fluid and elegant movements contrast with the darker, more tragic themes of the opera, offering a visual representation of the tension between temptation and morality. This balletic interlude not only heightens the dramatic intensity but also allows the music and choreography to reflect the hedonistic world that Faust is drawn into.

In popular culture

The legend of Faust has made numerous appearances across literature both directly – as in Christopher Marlowe’s 1592 Doctor Faustus and Gertrude Stein’s 1939 Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights – and indirectly, through allusions to Faustian pacts and attendant themes of temptation, moral compromise and the search for meaning.

In Edith Wharton’s 1920 novel The Age of Innocence, the Faustian theme is subtly woven into the narrative, particularly through the character of Newland Archer. Archer, like Faust, is torn between his duty and his desires. His inner conflict is mirrored in Faust's struggle to reconcile his quest for knowledge and pleasure with the consequences of his choices. Archer’s obsession with the forbidden love of Ellen Olenska, which ultimately leads to his personal disillusionment, can be seen as a modern, more restrained take on the Faustian pact. In the 1993 film adaptation of The Age of Innocence, directed by Martin Scorsese, the Faustian elements are further emphasised through visual cues, including the contrast between the suffocating, bourgeois world of New York society that Archer (Daniel Day Lewis) grows weary of and the liberating, yet dangerous allure of Ellen (Michelle Pfeiffer). The film highlights Archer’s moral dilemma, much like Faust’s, where his choices lead to a life of regret, despite the absence of an overt ‘deal with the devil.’

Gallery

Characters

Faust – An aging and despairing scholar who sells his soul to Méphistophélès in exchange for youth and pleasure. (Sung by a tenor)

Méphistophélès – The devil who tempts Faust and facilitates his desires. (Sung by a bass-baritone)

Marguerite – A beautiful and innocent young woman whom Faust seduces, leading to tragic consequences. (Sung by a soprano)

Synopsis

ACT I

Weary of life and the vain pursuit of knowledge, the aged Faust decides on suicide. He is stopped in his tracks by the light of dawn and voices singing God’s praises. Faust bitterly renounces God and calls on Satan. Méphistophélès duly appears. He will satisfy Faust’s hedonistic demands in return for the philosopher’s soul. Hesitating at the last moment before signing the diabolic contract, Faust is finally swayed by a vision conjured up by Méphistophélès of the beautiful and innocent Marguerite: Faust must have her.

ACT II

The town is celebrating. In their midst, Valentin is preoccupied with thoughts of leaving to fight in the war. He asks his friends to look after his sister Marguerite while he is away; among them is Siébel, who is in love with her. They are interrupted by Méphistophélès, who sings a blasphemous song and makes innuendos about Marguerite. This is too much for Valentin who is roused to defend his sister and attack Méphistophélès, but his sword breaks mid-air and everyone hastily withdraws. Méphistophélès is joined by Faust; when Marguerite appears she rejects Faust’s attentions.

ACT III

Siébel leaves a bouquet of flowers for Marguerite. Next, Faust extols the virtues of Marguerite’s home while Méphistophélès also finds something to leave her: a box full of jewels. Marguerite appears, lost in thought, but is overcome with excitement as she discovers the jewel box and tries on its contents. Marthe Schwertlein, Marguerite’s neighbour, thinks that the jewels must be from an admirer. When both women are joined by Méphistophélès and Faust, the former distracts Marthe so that Faust can seduce Marguerite.

ACT IV

Five months have passed. Marguerite has been deserted by Faust, but is carrying his child. In church, her prayers are repeatedly interrupted by demons. She faints as Méphistophélès’s final curse denies her the hope of salvation. Soldiers return from the war, Valentin among them. He asks Siébel to tell him how his sister is, but Siébel’s evasions prompt him angrily to rush into Marguerite’s house to find out for himself. Méphistophélès and Faust arrive, and the Devil satirically serenades Marguerite. Valentin emerges from the house demanding to know who is responsible for his sister’s shame. In the ensuing duel, Faust mortally wounds Valentin, who with his final words denies Marguerite any Christian compassion and damns her for eternity.

ACT V

It is Walpurgis Night and a diabolic ballet ensues. Faust is subjected to visions, the last of which is of Marguerite in prison for the murder of their child and awaiting execution. Faust wants to go to her, and Méphistophélès obliges. Together in the cell, Faust and Marguerite remember their shared moments of love and Faust urges her to flee with him, but she resists, calling for divine protection. Marguerite’s supplication is answered: her soul ascends to heaven.

Watch now

- Main Stage

Faust

- Opera and Music

A deal with the devil. What could go wrong? Watch Gounod's spectacular opera of decadence and debauchery on the Main Stage

Royal Opera House Covent Garden Foundation, a charitable company limited by guarantee incorporated in England and Wales (Company number 480523) Charity Registered (Number 211775)