The Tales of Hoffmann

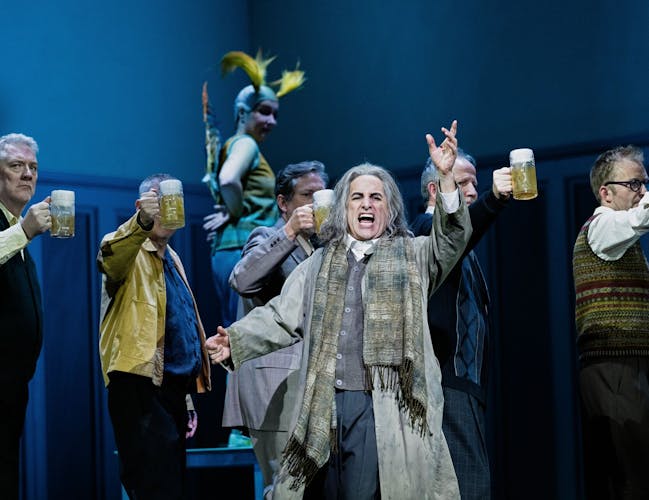

Our quick guide to Damiano Michieletto's new production of Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann.

The Tales of Hoffmann is an opera by Jacques Offenbach based on three short stories by E.T.A. Hoffman, each of which tells the story of a different tale of love. In the opera, the central character, Hoffmann, is a fictionalised embodiment of E.T.A. Hoffmann. Each of the three stories unfolds as flashbacks from Hoffmann’s romantic past – although as the opera goes on, it becomes clear that memory and fantasy are becoming increasingly blurred.

Quick Facts

Who wrote the opera The Tales of Hoffmann?

Jacques Offenbach wrote the music for The Tales of Hoffmann. The libretto was written in French by Jules Barbier. It is based on three short stories by the writer E. T. A. Hoffmann, who is the fictionalised protagonist of the opera. The Royal Opera currently perform a production directed by Damiano Michieletto.

Who are the heroines in The Tales of Hoffmann?

Journeying back to his school days, Hoffmann relives his childhood romance with Olympia, a model student in every sense. Doomed love follows him into adulthood, where the dancer, Antonia, is taken from him too soon. Meanwhile, the sensual courtesan Giulietta has her own secret agenda. A fourth love, Stella, is the object of his fascination in the poet's old age – but all is not as it seems.

What is the famous duet in The Tales of Hoffmann?

Among the duets, the best known is perhaps the sensual barcarolle-style ‘Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour’ (Beautiful night, oh night of love), that opens the Giulietta act. It is sung by Giulietta and Nicklausse.

How long is The Tales of Hoffmann?

The Tales of Hoffmann lasts approximately 3 hours and 35 minutes, with two intervals.

History

A journey across the channel

The Tales of Hoffmann was Offenbach's final work; he died in 1880, four months before the premiere. He had enjoyed fame across Paris with his many amusing and often risqué operettas, occasionally poking fun at his fellow composer, Richard Wagner. The central character in The Tales of Hoffmann is based on the real-life writer and poet E.T.A Hoffmann, who is most famous for writing the story that inspired the classic Christmas ballet, The Nutcracker. The Tales of Hoffmann is based on three of Hoffmann's own short stories: Der Sandmann (The Sandman), Rath Krespel (Also known as Councillor Krespel or The Cremona Violin) and Das verlorene Spiegelbild (The Lost Reflection) from Die Abenteuer der Sylvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year’s Eve).

The opera first reached London in 1907 with a production at the Adelphi Theatre in 1907 and another at His Majesty's Theatre in 1910. The first production to be commissioned for Covent Garden had its premiere in 1932 and included magical effects by conjuror and illusionist Noel Maskelyne. After this, there was interest in creating English-language versions. This included a new version for Covent Garden by Günther Rennert and a film produced and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1951.

The Tales of Hoffmann Synopsis

Characters

- E.T.A Hoffmann – a writer (sung by a tenor)

- Nicklausse – his companion (sung by a mezzo-soprano)

- Stella – an opera singer (a silent role)

- Olympia – Hoffmann's first love (sung by a soprano)

- Antonia – Hoffmann's second love; a performer (sung by a soprano)

- Guilietta – Hoffmann's third love; a courtesan (sung by a mezzo-soprano)

- Lindorf/Coppélius/Dr Miracle/Dapertutto - the devil (sung by a baritone)

- The Muse of Poetry (sung by a mezzo-soprano)

- Coppélius – the spectacle maker (a tenor)

- Spalanzani – an inventor (a tenor)

The Muse of Poetry descends among the Spirits of Wine. Stella, a beautiful opera star, has captivated the poet Hoffmann. The envious Muse orders the Spirits to help her dispose of Stella’s unwanted influence. She summons Nicklausse as a companion for Hoffmann.

A group of students arrives for refreshments during the interval of Don Giovanni. Hoffmann, preoccupied with his love for Stella, joins them, accompanied by Nicklausse. The students coax Hoffmann into telling the tale of Kleinzach. Tensions rise between Lindorf and Hoffmann: whenever the poet encounters Lindorf he is beset by misfortune. The poet relates the tales of his three loves.

The young Hoffmann is a pupil of the inventor Spalanzani. Hoffmann is in love with Olympia, whom he takes to be Spalanzani’s daughter. Coppélius the spectacle-maker arrives. Hoffmann gazes at Olympia through a pair of his glasses and is overcome by her beauty. Spalanzani makes a deal with Coppélius, to buy out his stake in Olympia.

Others arrive. Spalanzani presents Olympia to them as his daughter and Olympia sings, to great acclaim. Alone with Olympia, Hoffmann becomes convinced that she loves him. Coppélius returns, enraged that Spalanzani has cheated him. He takes revenge by destroying Olympia. Hoffmann realises at last that she was nothing but a mechanical doll.

Crespel has whisked his daughter, Antonia, away to Munich, far from Hoffmann. She is ill, and it could be fatal for her to perform. Hoffmann arrives unannounced, desperate to find out the reason for Antonia’s departure. She tells him that her father no longer permits her to perform. Hearing Crespel return, Hoffmann hides. Dr Miracle arrives, to Crespel’s dismay: he remembers the part Miracle played in the death of his wife.

Hoffmann now understands Crespel’s motives, but he keeps them secret. Instead, he urges Antonia to abandon hope of future glory as a performer. Miracle tries to lure Antonia into performing. She resists until he conjures up a spirit resembling her mother. Antonia gives way. Miracle accompanies Antonia while she performs. She collapses. Crespel accuses Hoffmann of causing his daughter’s death. Miracle returns to confirm that Antonia is dead.

In a Venetian Palace, Hoffmann declares he is through with love. Schlemil escorts the courtesan Giulietta into the gaming room. She invites the other guests to join her. The demonic Dapertutto uses a sparkling diamond to summon Giulietta. He commands her to seduce Hoffmann and steal his reflection (or soul). Giulietta’s conquest of Hoffmann is quick, yet when the poet realises what has happened, he remains infatuated with her.

Back in the tavern Hoffmann reveals that the three stories are different aspects of the same woman: Stella. Lindorf now realises that he has nothing to fear from his rival.

The Muse sings a song of reassurance: through his suffering Hoffmann's poetic art will flourish and he will eventually belong to her.

Pictures and Videos

Gallery

The Doll Aria

‘Les oiseaux dans la charmille’, also known as the Doll Aria from The Tales of Hoffmann, is infamously difficult to sing. It is sung in Act I by Olympia, a mechanical doll who the hapless Hoffmann believes to be human. For much of the act, Olympia simply says ‘oui’ (yes) to anything asked of her, but Offenbach more than makes up for this in her aria. Written for the French soprano Adèle Isaac – a star of Paris’s Opéra-Comique known for her interpretations of challenging roles such as Marie (La Fille du régiment), Isabelle (Robert le diable) and Juliette (Roméo et Juliette) – it is a virtuoso tour-de-force. When Olympia performs her song for Spalanzani’s party guests, Hoffmann is so impressed that he determines to marry the doll.

Offenbach’s music perfectly characterizes a mechanical doll, with a pretty melody sung to a waltz rhythm, and delicate harp and flute accompaniment reminiscent of the sound of musical boxes. However, Olympia's melody line becomes progressively more ornate. She pays the price for this display though – during both refrains her mechanics run down, causing her to collapse until Spalanzani winds her up again. The second time, he clearly does his job rather too well, as Olympia soars to new heights in the hyperactive closing lines.

The Barcarolle

Among the many duets in The Tales of Hoffmann is the sensual Barcarolle ‘Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour’ that opens the third, Giulietta act. This act is set in Venice, where this music comes from. A barcarolle is a song traditionally sung by gondoliers in Venice. The word, ‘barcarolle’, derives from the Italian word, ‘barca’, meaning ‘boat’. The lilting rhythm of Offenbach’s barcarolle (in six-eight time), evokes the lapping of the water.

Offenbach's most famous work may be the 'can-can' but the Barcarolle itself has become recognisable through its use in film and tv. The 1997 WWII-themed Italian film Life is Beautiful uses 'Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour’ as a theme throughout. It is firstly used when Guido, a Jewish-Italian waiter, sees Dora, the woman that he loves, at the opera. Later, after they have both been taken to the concentration camp, Guido plays the piece on a record player, hoping that his wife hears across the camp walls.